Every time I ship a new feature, someone asks the same question: “Are you planning to localize the app into more languages?”

I write my apps primarily in English and Simplified Chinese. Over time, I’ve received requests for French, German, Spanish, and more. A few generous users even offered to help translate.

I always thank them for their generosity—but always chose to decline and for a very practical reason: my apps ship frequently. I can’t afford to wait for localization before releasing features. If localization becomes a blocking step, it stops being a quality improvement and turns into technical debt.

Shortly before the holiday season, I shipped Woolly, a free gift card tracker app that I built in 8 days. I used Woolly as my genie pig on the AI–powered localization process, and I learned a lot.

I realized the problem wasn’t translation at all, but system design.

The false problem: “We need better translations”

Most localization conversations start at the wrong place. We talk about string quality, translation accuracy, and native-sounding phrasing. Those things matter—but they’re downstream concerns.

If your app embeds numbers, dates, currencies, measurements, and formatting rules directly into strings, you’ve already lost. No amount of translation polish can save a system that fundamentally doesn’t understand locale.

That’s because language is only one layer of localization.

There are many factors that make an app feel localized. The app should obviously speak the language. It should also display numbers and date-time values in the widely accepted format. On top of all that, it should respect any preferences the user may have.

A few examples:

- Decimals and thousand separators:

1,234.56vs1 234,56vs1.234,56. - The same 5 US dollars may show up as

$5.00in the US,US$5.00in Canada, or5,00 $ USin France. - Weeks may start on Sunday or Monday.

- The user may prefer 12-hour over 24-hour time.

- Spelling (see above meme) and word choice (eggplant vs aubergine)1.

- Punctuations, including “this” vs «that»; and a non-breaking space before

?,!or:in France, vs the lack of that in Canadian French.

None of these are translation problems; they are convention problems, and more importantly, problems that the operating systems already know how to solve!

It’s the hard truth: most localization bugs are not caused by translators or LLMs; they are caused by developers overriding the system.

So surprisingly, my first lesson about the LLM–powered localization process? It’s not about LLM at all! It’s that you should design your app and delegate as much to the system as possible.

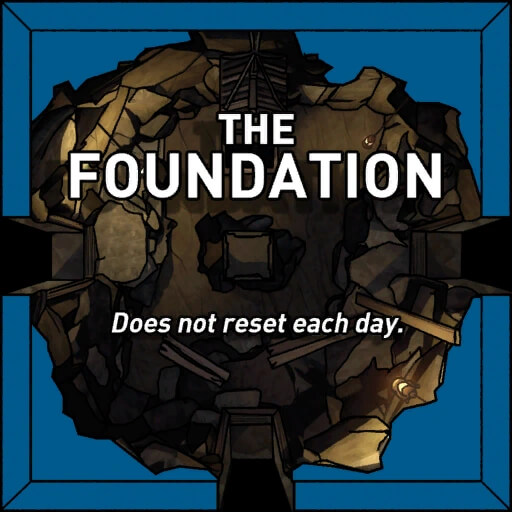

In the Apple ecosystem, that package is the Foundation framework.

The Foundation framework

The Foundation framework dates back decades. Many of the implementations existed way before Swift, or iPhone for that matter, was a thing. You should delegate date formatting to the DateFormatter class, and delegate number and currency formatting to NumberFormatter.

Formatting dates

Date formatter makes it easy to format dates based on the components you want. For example, this method below may give you “Sep 21, 2025”:

func displayDate(for date: Date) -> String {

let formatter = DateFormatter()

formatter.setLocalizedDateFormatFromTemplate("MMMdyyyy")

return formatter.string(from: date)

}

The template symbols used all follow ISO 8601 standards. You can find the list of symbols here.

Some subtle traps even experienced devs hit:

- Prefer

jfor hours instead ofhorH. It respects the user’s 12- or 24-hour preference automatically. - Avoid uppercase

Yunless you truly want the “week-of-year” calendar year. - Use

L(standalone month) vsM(month in date context) intentionally. - Let the system decide symbol ordering—template order doesn’t matter.

Formatting numbers

It’s easy enough to format a decimal for the current locale:

func formatNumber(_ decimal: Decimal) -> String? {

let formatter = NumberFormatter()

// formatter.locale = .current // This is implied

return formatter.string(from: decimal as NSDecimalNumber)

}

You can also specify the locale property of the number formatter. The formatter uses Locale.current by default.

It’s similarly easy to format a currency:

func formatNumber(_ decimal: Decimal) -> String? {

let formatter = NumberFormatter()

formatter.style = .currency // Add this line

formatter.currencyCode = "USD" // And this line

return formatter.string(from: decimal as NSDecimalNumber)

}

The number formatter considers the locale (both the language and the device region) and the currency. These are some of the results I’m able to get for 5 US dollars:

| Locale | 5 US Dollars |

|---|---|

| US English | $5.00 |

| Canadian English | US$5.00 |

| French | 5,00 $ US (the decimal point, and space around the dollar sign) |

| German | US$ 5.00 (space after the dollar sign) |

| Spain (Region = Canada) | USD 5.00 (spelled out “USD”) |

| Spain (Region = US) | $ 5.00 (only a dollar sign and a space; US is implied and omitted) |

Imagine nailing all the details yourself! Whew.

Finally, there are currencies where there aren’t fractions, such as Japanese Yen or Korean Won. Number formatter automatically rounds up or down any fraction values for you, so you end up with, for example, JP¥100 but never JP¥100.00.

Side note — in SwiftUI, you can also use a convenience with Text(:, format:):

Text(5.00, format: .currency(code: "USD"))

This initializer doesn’t do all the things a Number Formatter can do, but it’s an option.

Other formatters

In recent years (relatively speaking), Apple added more formatters including MeasurementFormatter and DateIntervalFormatter. The former helps you do unit conversion (e.g. kilometres vs miles) and may choose a more natural scale (e.g. 10 centimetres instead of 0.0001 kilometres). The latter can omit shared date components when describing a date range so the result reads more naturally.

If those interest you, you can find out more yourself with Apple’s documentations and WWDC videos.

When “almost perfect” can be worse than “obviously machine-made”

I enlisted a friend to help check the Japanese localization of the app, and he really gave me something to think about on perfection. In his words, I shouldn’t be telling the user to stop doing something, as this can come across too harsh. Then he paused, and said, “hmm, I think it’s fine because you are a foreigner,” and that my users would be forgiving to the tone because they’d know it’s written by a non-native speaker (or rather, by a machine).

This is the uncanny valley in localization: right now, LLM-generated localization feels about 75–80% as good as professional native copywriting. That might be a sweet spot. When users know something is machine-generated, they’re forgiving. Slight stiffness reads as neutral, not wrong. Simple wording feels intentional.

But what happens when we reach 90–95%? These cultural errors stand out more than obvious automation ever did. And what is perfection then? It points back to systems: predictable, boring, consistent output beats cleverness.

-

A personal anecdote: I added “rockets” to my bagel for 1 pound in London, UK, just to see what they are. They turned out to be arugula! ↩